withering…

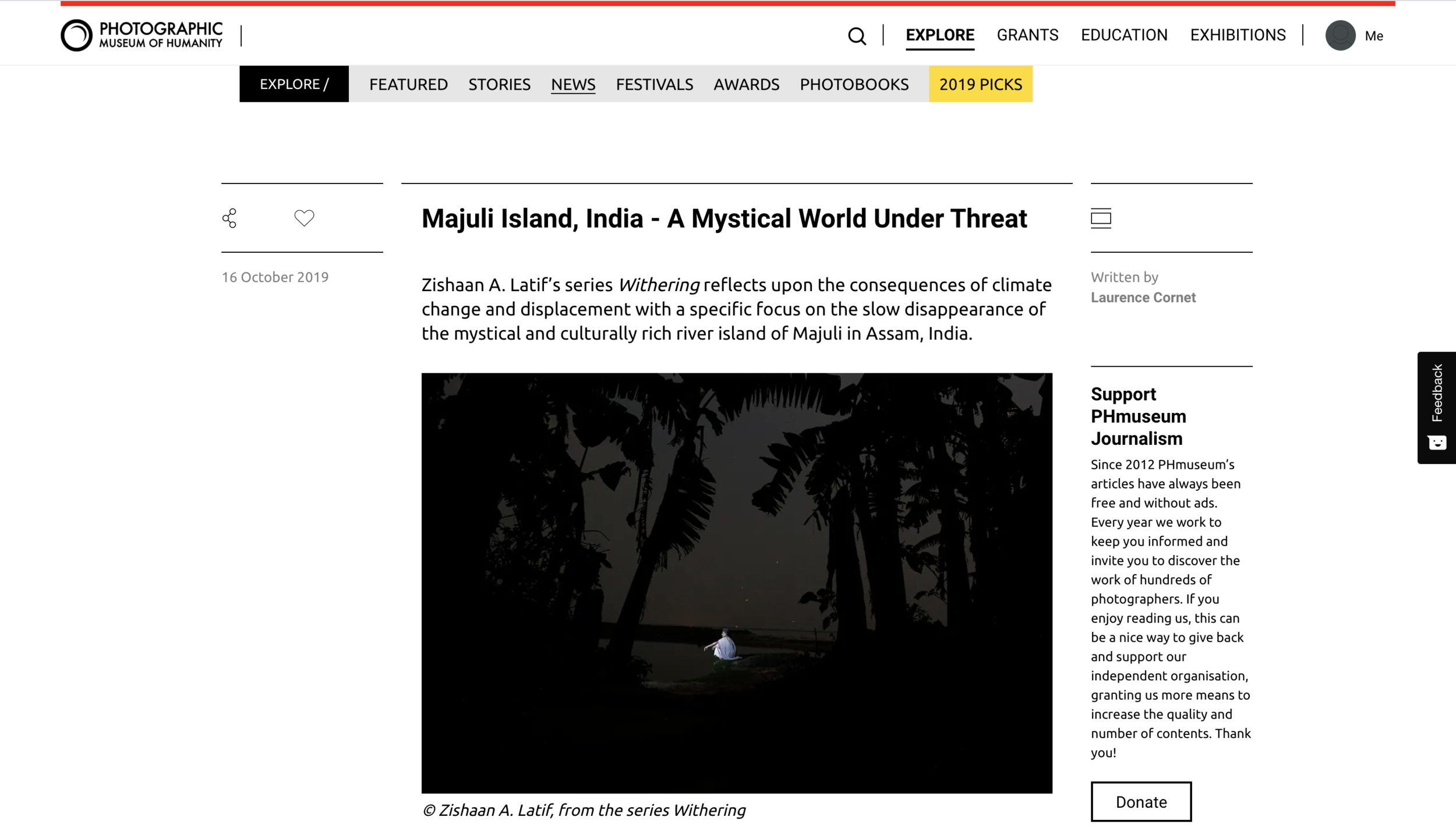

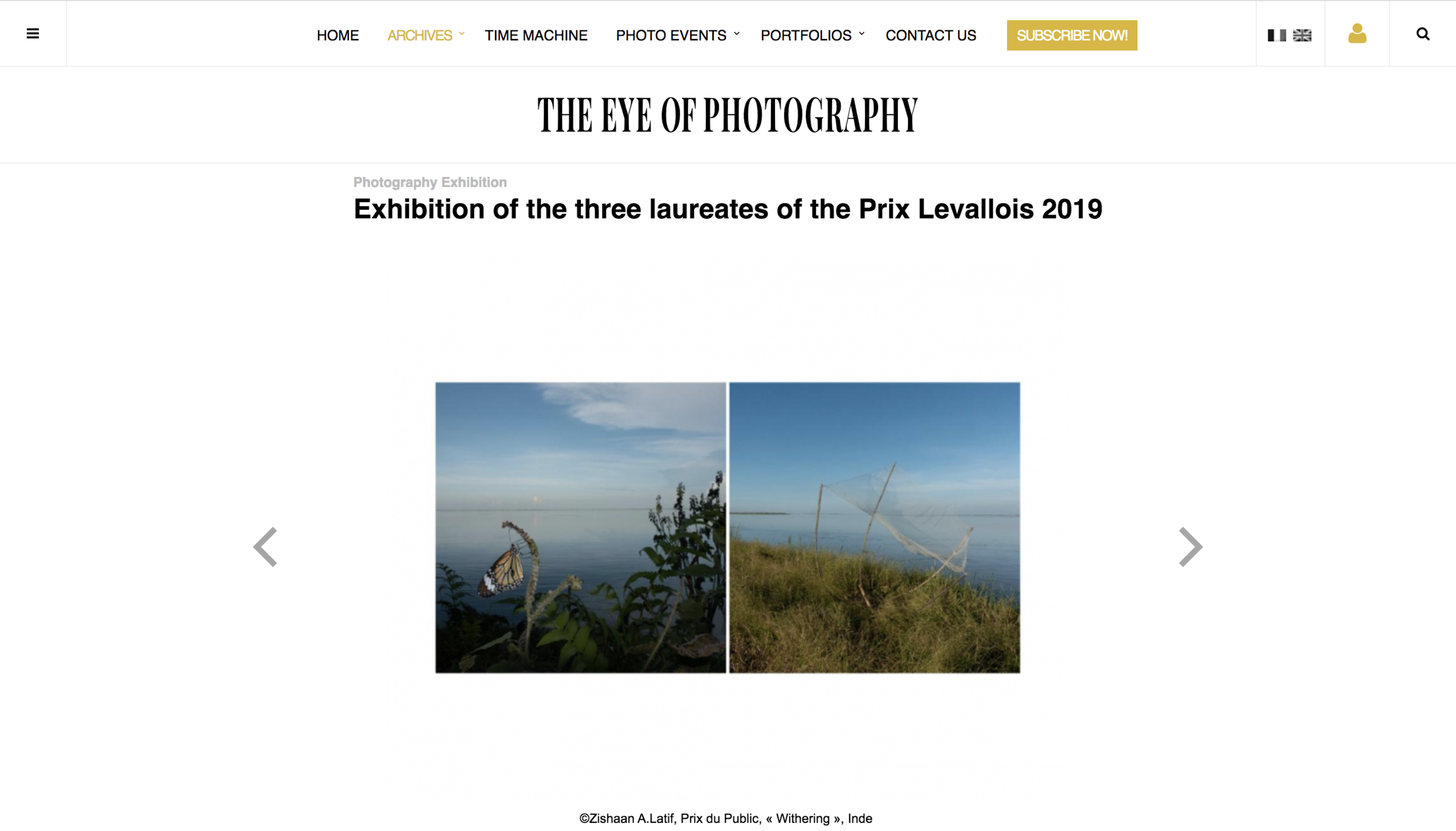

Withering is an endeavour to document the 'drowning state of existence' of the river island of Majuli in Assam. It is a catastrophe caused by the aggressive Brahmaputra. The aim is to reflect on the larger consequence of climate change and displacement. A segue of this project is the documentation of a disappearing, mystical and culturally rich environment; an organic community which presents itself as an alarming example of the issue of sustainability that the world must take cognisance of.

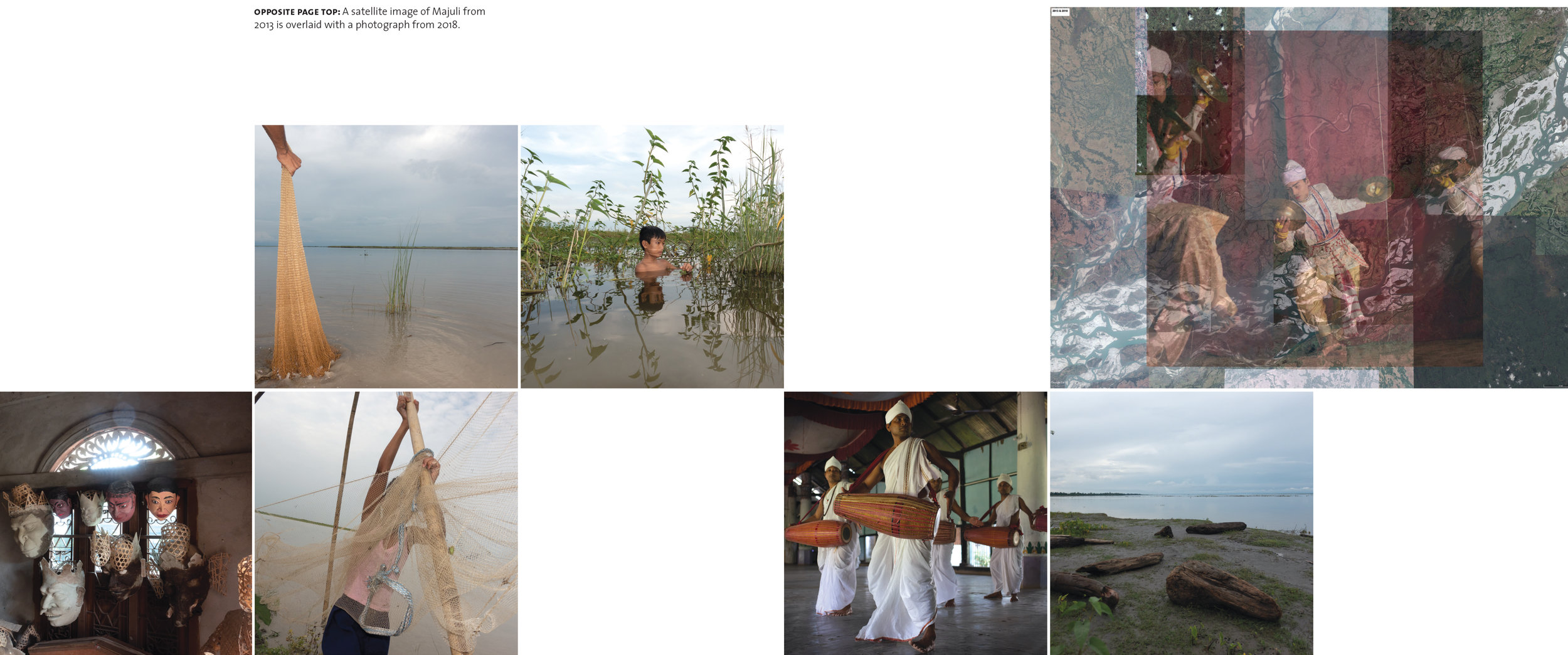

On the island, we traverse a fading ancient culture, the desperation to be afloat, a human engagement with nature palpable in their routine as they plough their fields, fish and weave tradition into the everyday, which make them feel alive even if for that moment, yet that silence persists, an all pervasive calm before the storm.

Majuli, in the river Brahmaputra, is the largest river island in the world. Organic agro-farming is the primary occupation of most of the 1.70 million residents, mainly of the Mising, Deori, Sonowal and Kachari tribes. The island is widely regarded as the cradle of the Ahom civilisation and the fountainhead of neo-Vaishnavism in Assam, India.

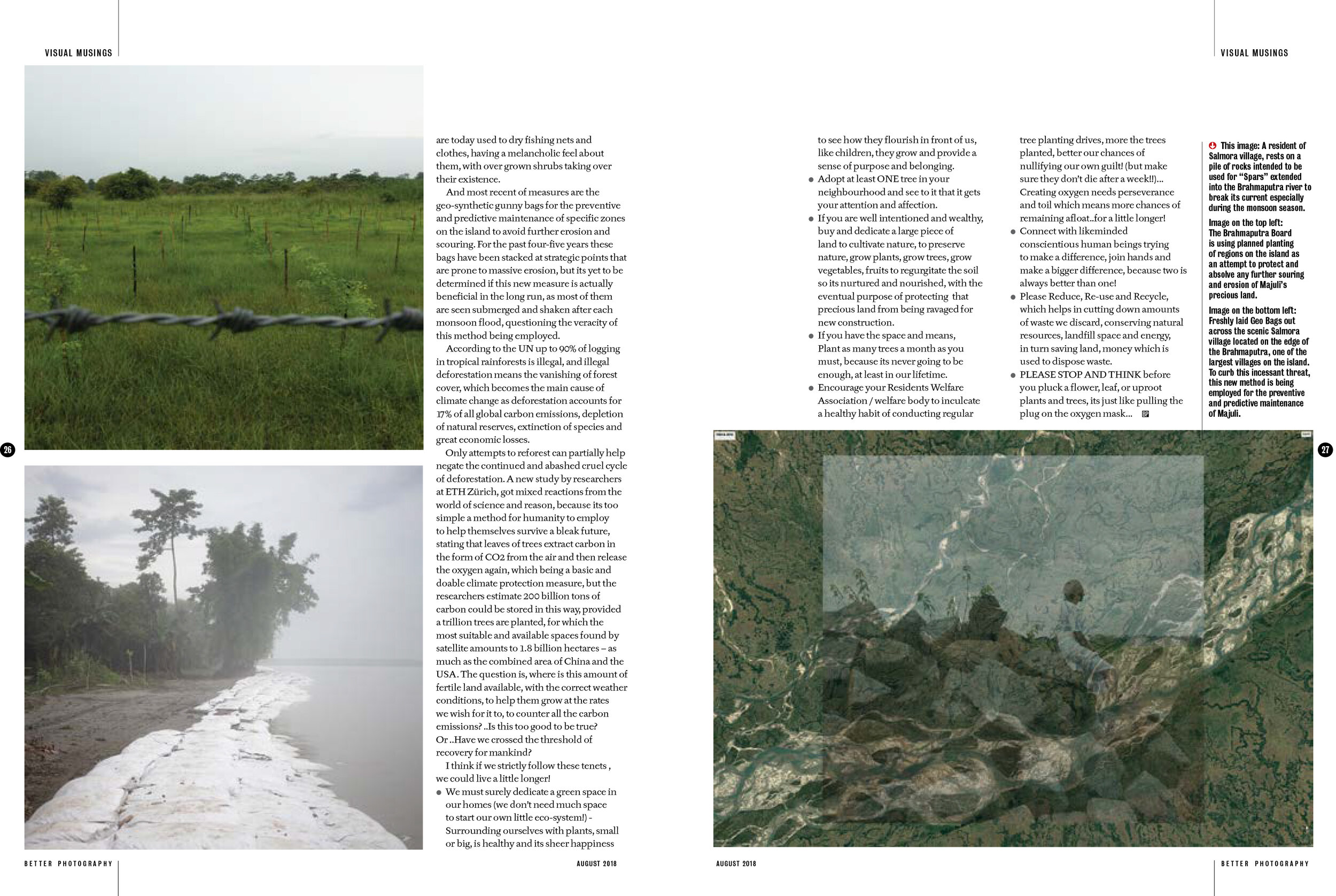

The 2,900 km river originates in Tibet as the Tsangpo, flows through Arunachal Pradesh as the Siang, and becomes the mighty Brahmaputra in the Assamese plains. It is prone to catastrophic flooding every year when the Himalayan snowmelt combines with unrestrained monsoon downpours. The evidence of climate change is harsh and rapid on the island as it is disappearing faster today, than ever before.

Today, Majuli faces extinction due to erosion. Huge chunks of the island are falling off into the Brahmaputra - its landmass is down by a third already! According to records, in 1800 the total area of Majuli was 1,150 sq. km. and about 33% of this landmass eroded in the latter half of the 20th century. The most recent satellite imagery from 2016 shows the island's landmass at just 524.29 sq. km.

The causes of this mass devastation are innumerable. Complications, including ill-planned construction and dams, lead to agitated waterways and irreversible damage. To add to this, corruption is rampant through the blatant misappropriation of funds meant to be allocated for prevention and rebuilding purposes.

People quietly rebuild their lives over and over, watching the establishment’s futile efforts to manage the disaster and knowing that they must work with nature, not against it. From the overcrowded ferry manoeuvring to avoid the shifting sands, one sees how the river slices through land, constantly eroding from one bank to deposit on another, without design or purpose.

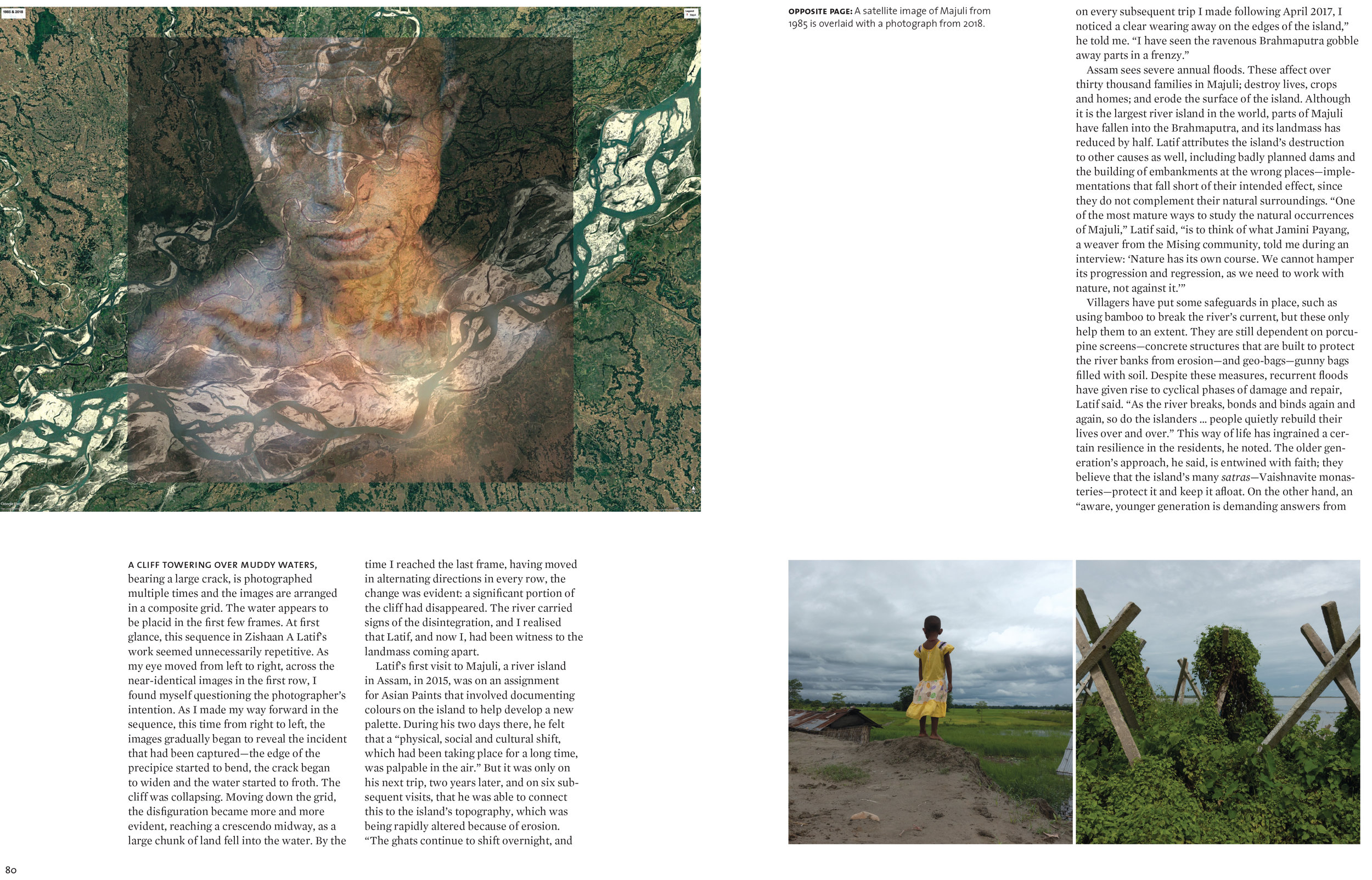

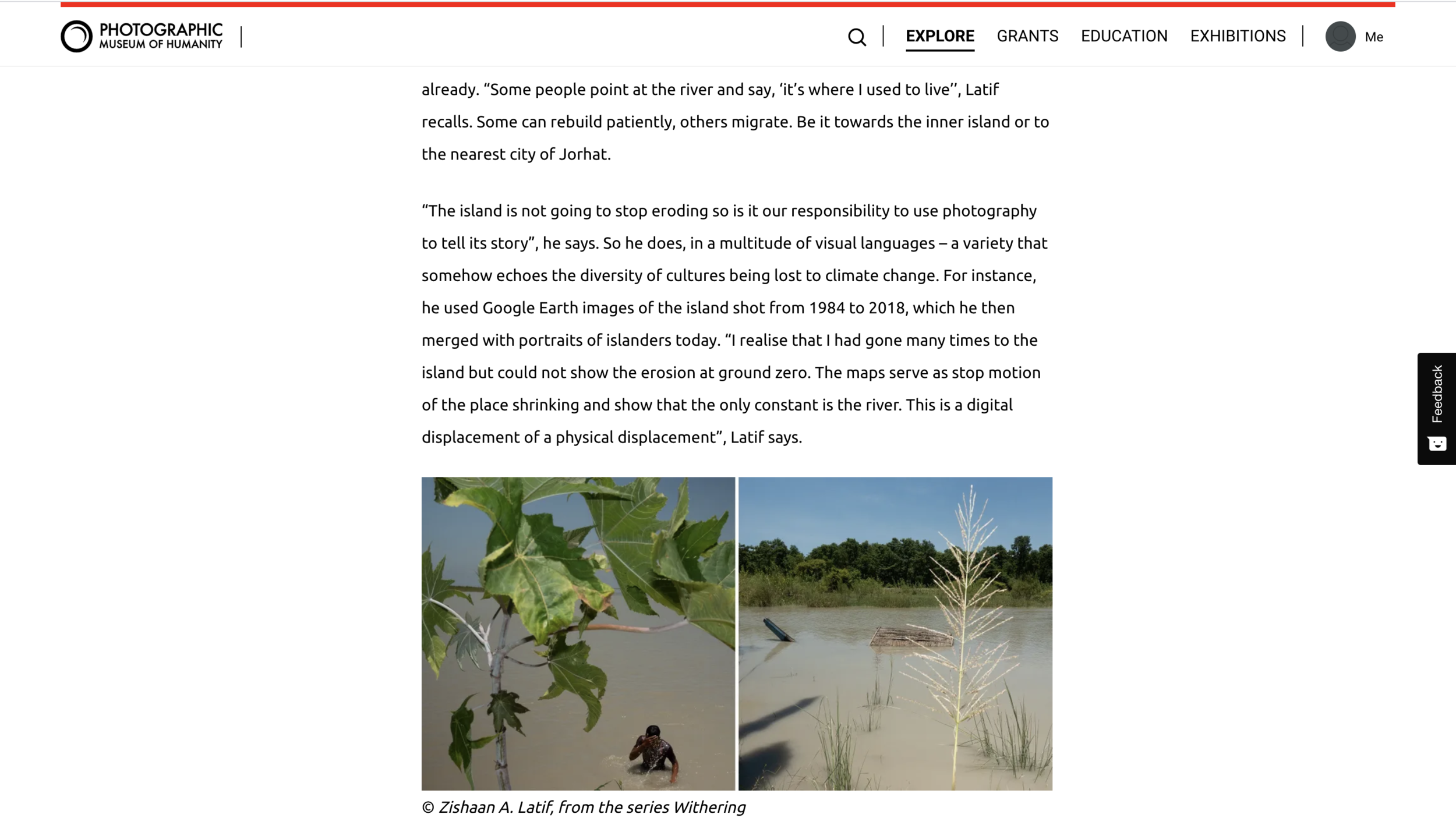

BREAKING - On the 26th of September 2018, I stood on the edge of civilisation, feeling the ground beneath me giving way, an uneasy experience, an eerie silence broken by the thump of terra firma being gobbled by a ravenous Brahmaputra, all before me, a witness to change, a witness to the truth called ‘erosion’, being consumed by the beauty and the beast of nature.

An instinct to lift my camera with an attempt to pause the breaking away was quick. As the river burst into action, so did I , but I couldn’t catch up with the forces, a harsh reminder of the attributes of nature but also the power it can unleash, when irked.

Each year the river swells and floods ever so fiercely, leaving a trail of destruction and displacement much worse than the previous year. Almost each year, the flood affects over 30,000 families of 246 villages on the island and washes away crops, mainly rice fields on 2,000 plus hectares. Since 2001, more than 3,000 families have lost their land to erosion and were forced to relocate. However, embankments are still home to more than 2,000 families.

(Photographed on the edge of a Mising Tribe village called Misa Mora, (Karoti Par), situated on the north western banks of Majuli, with a population of about 350 inhabitants.)

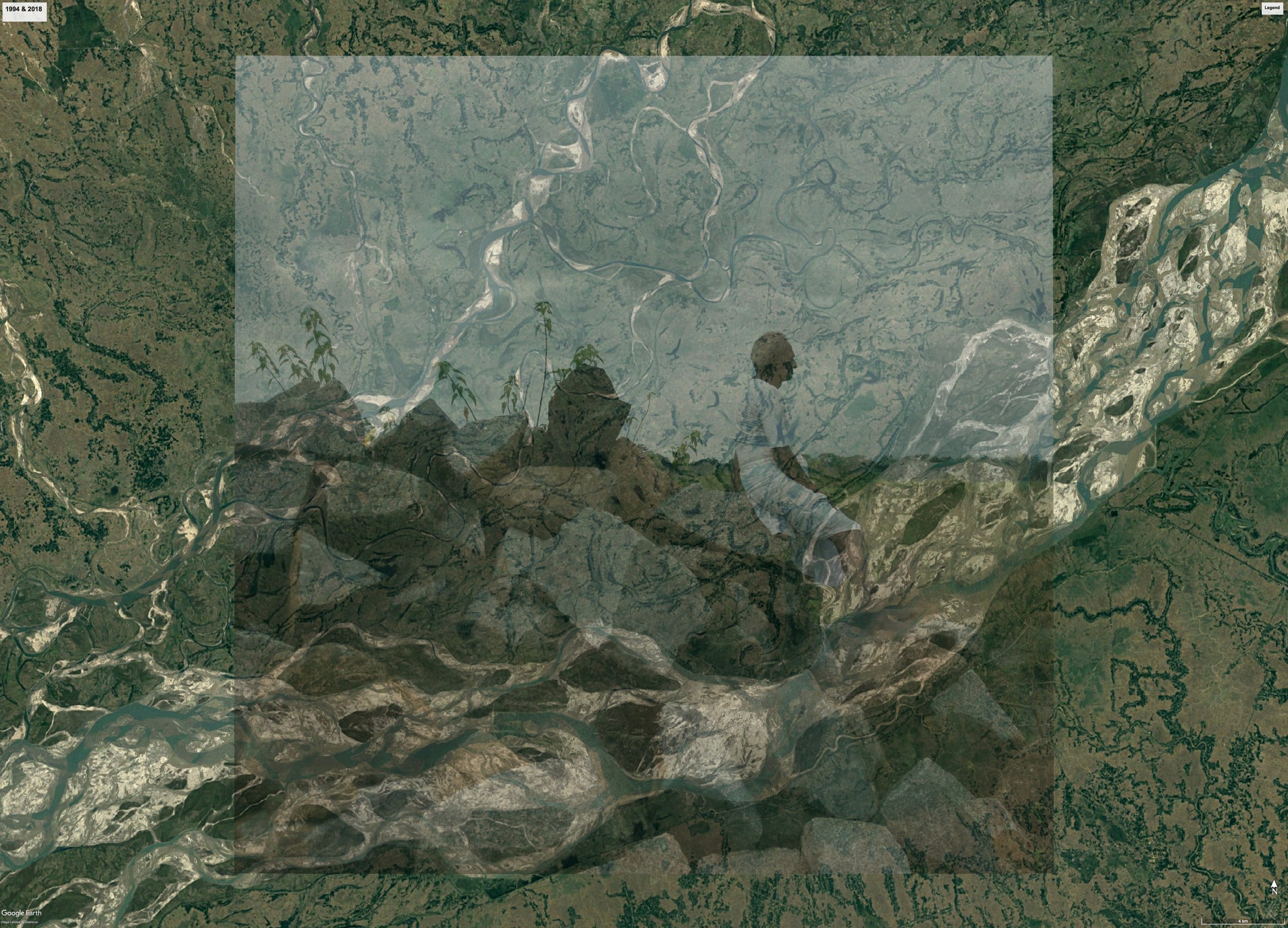

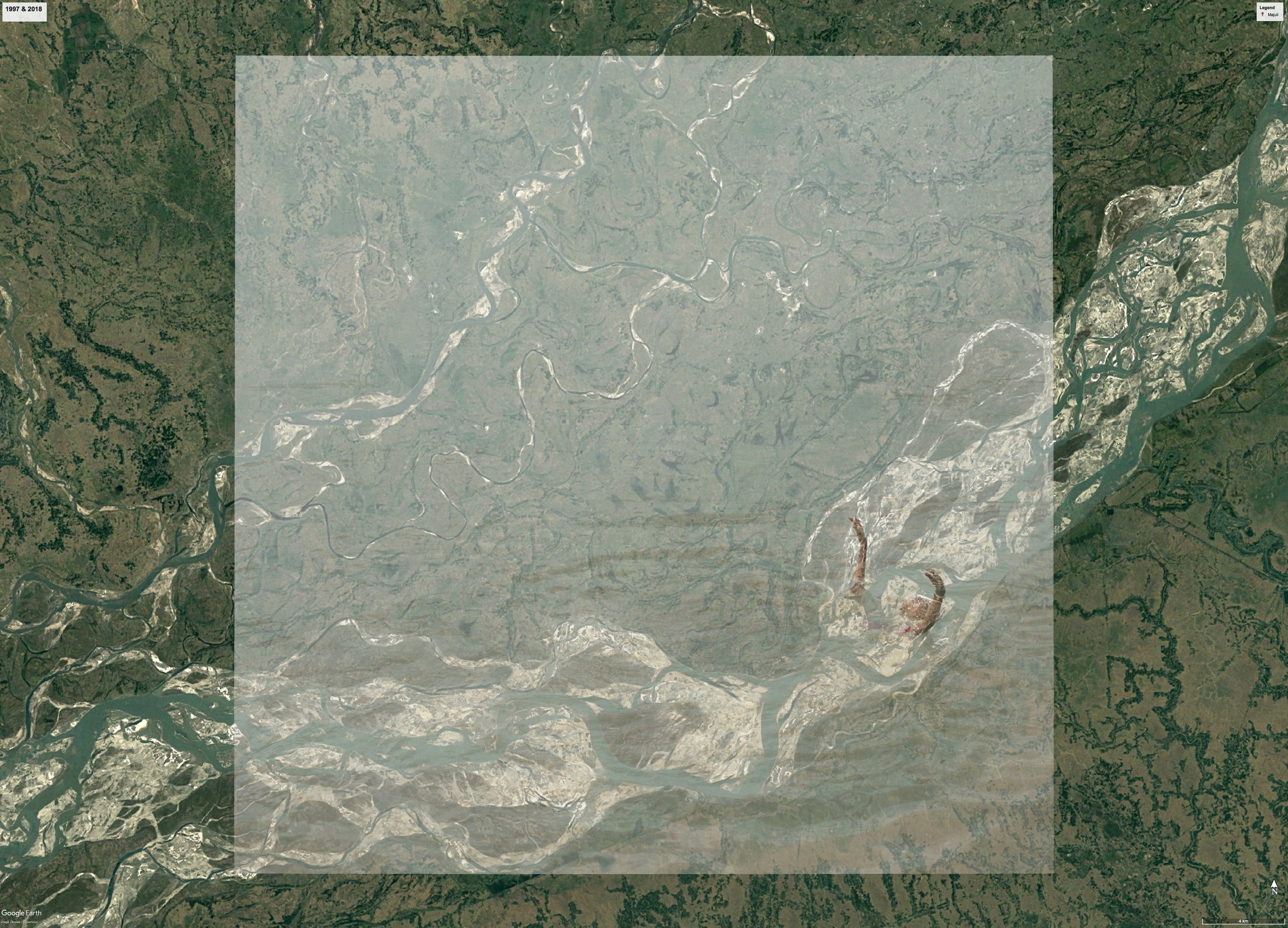

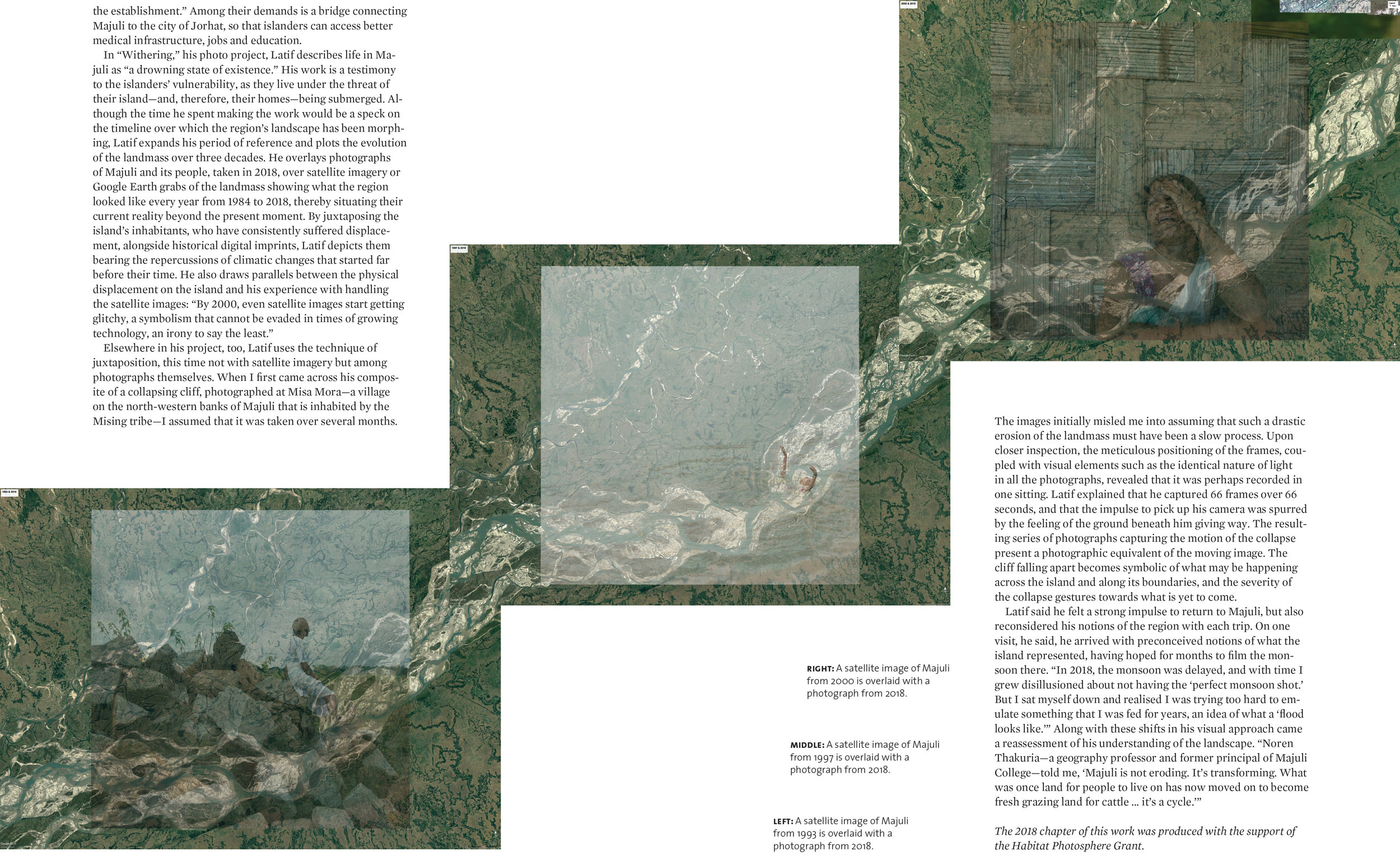

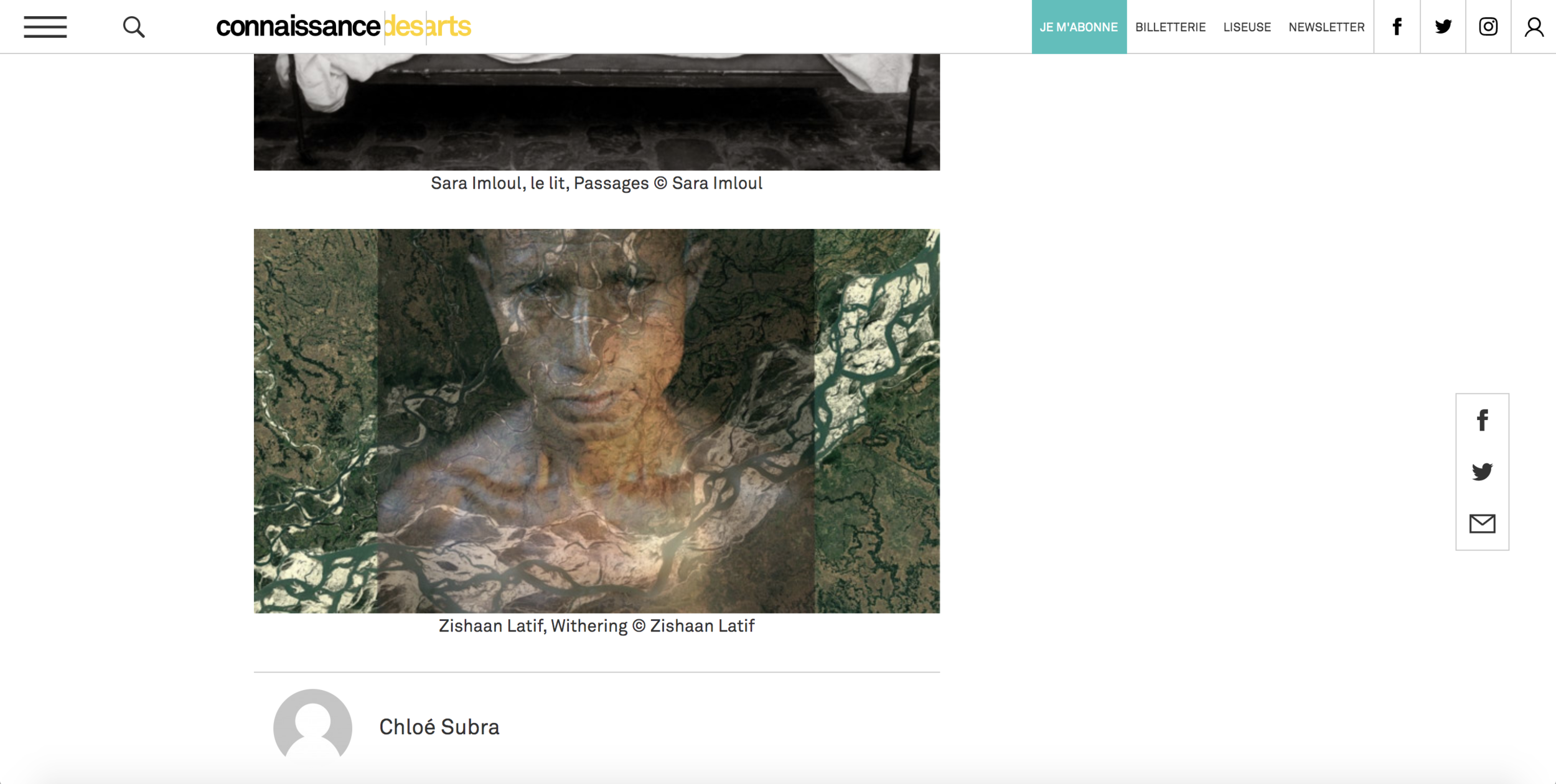

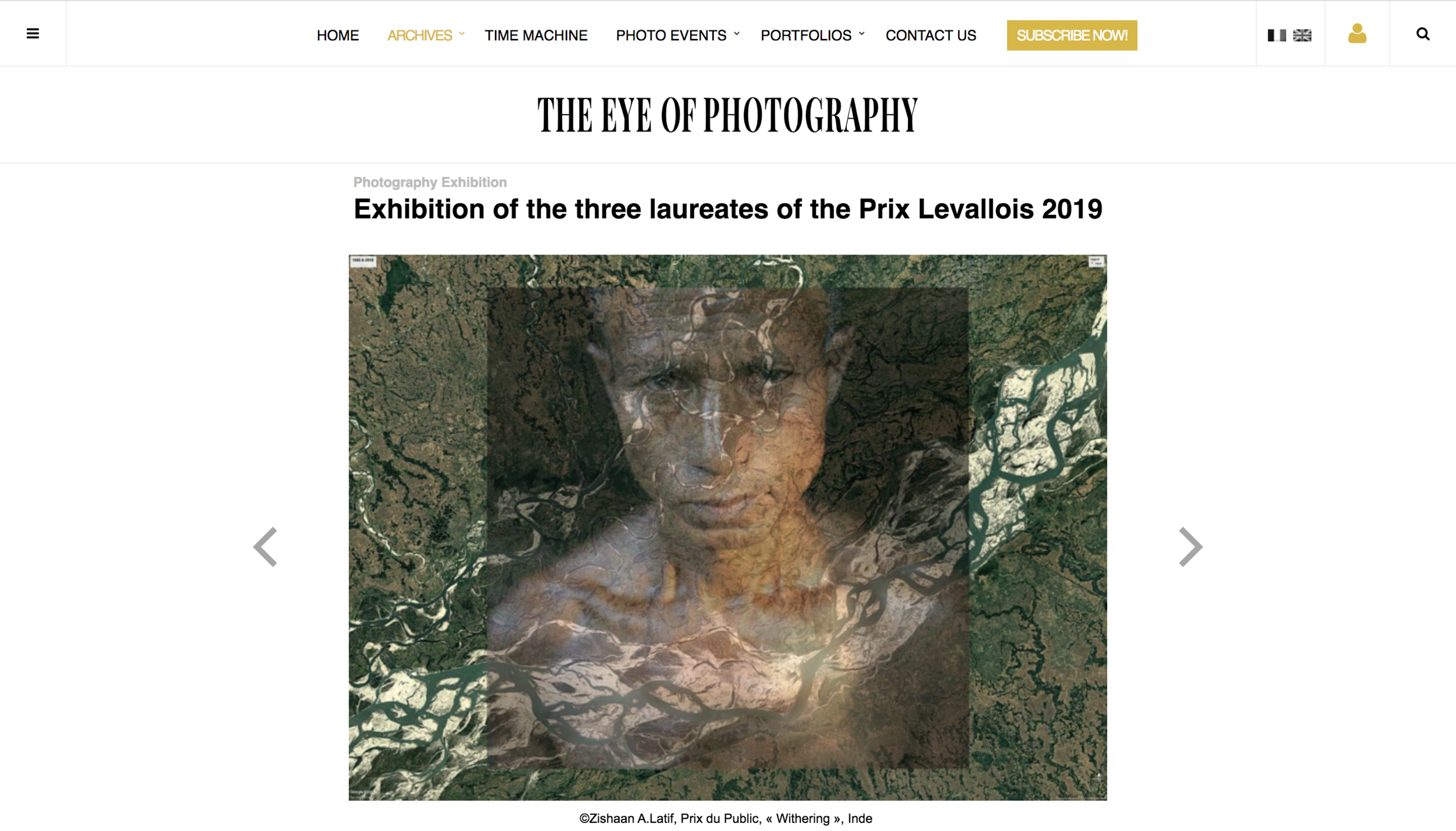

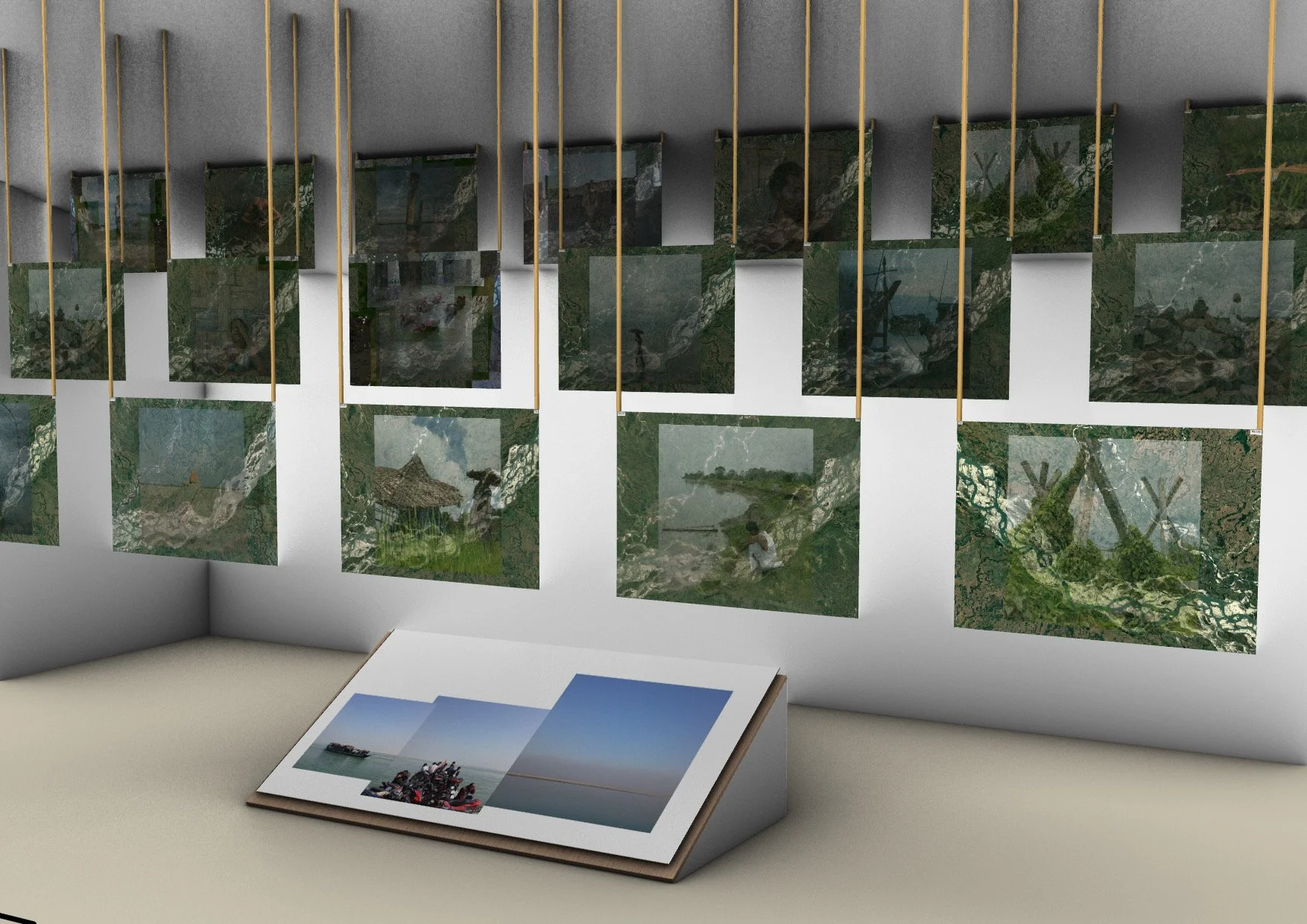

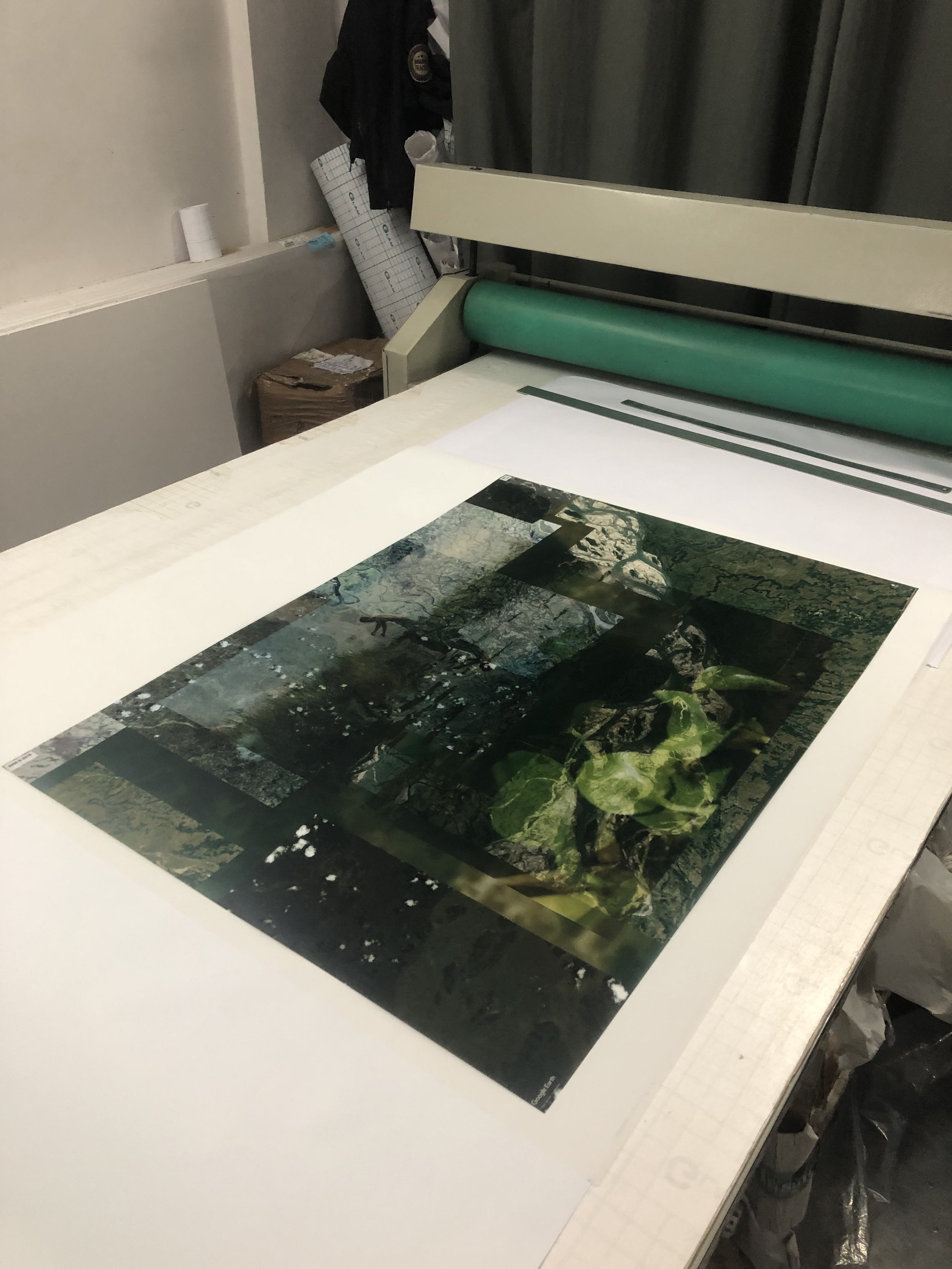

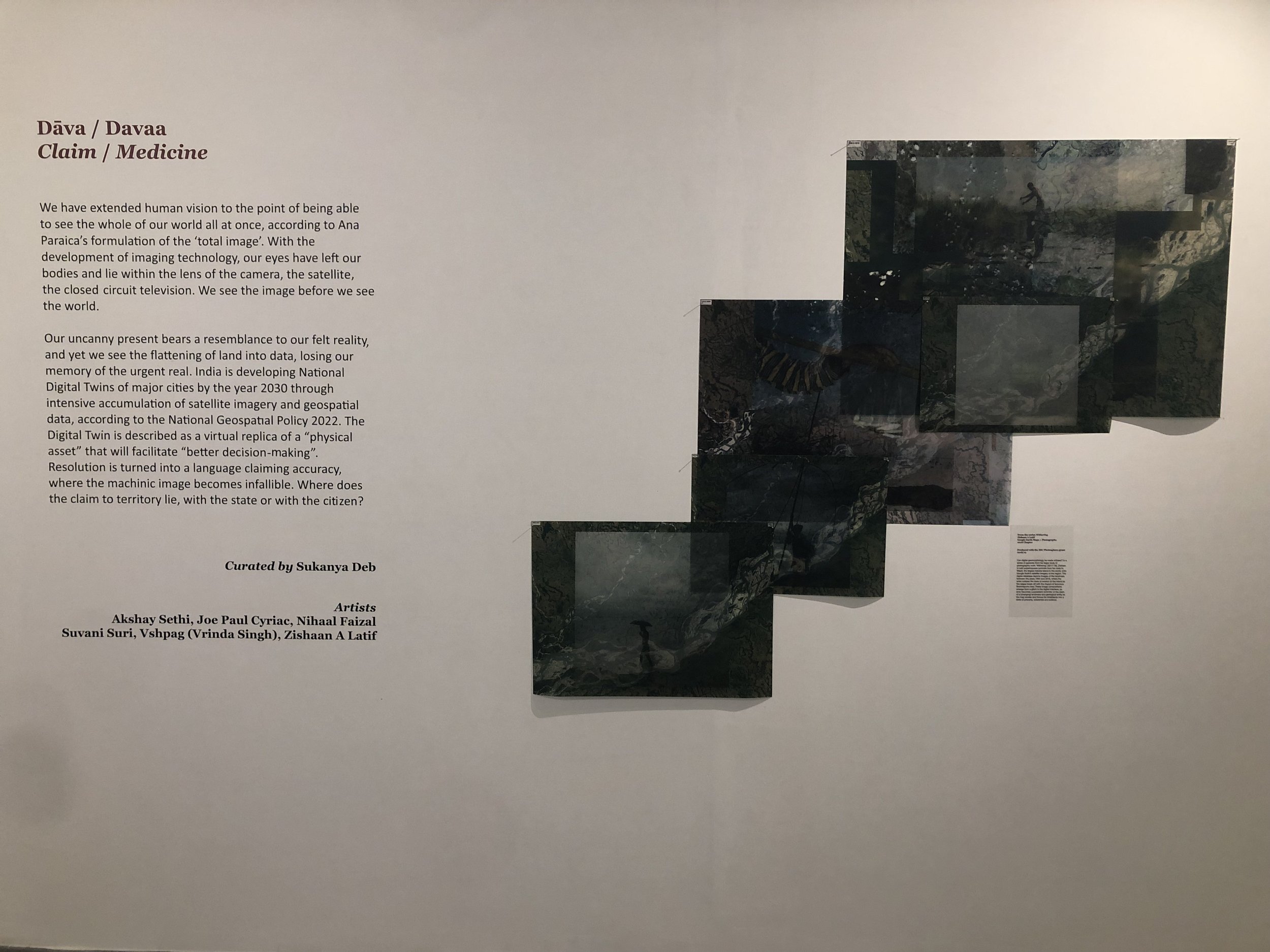

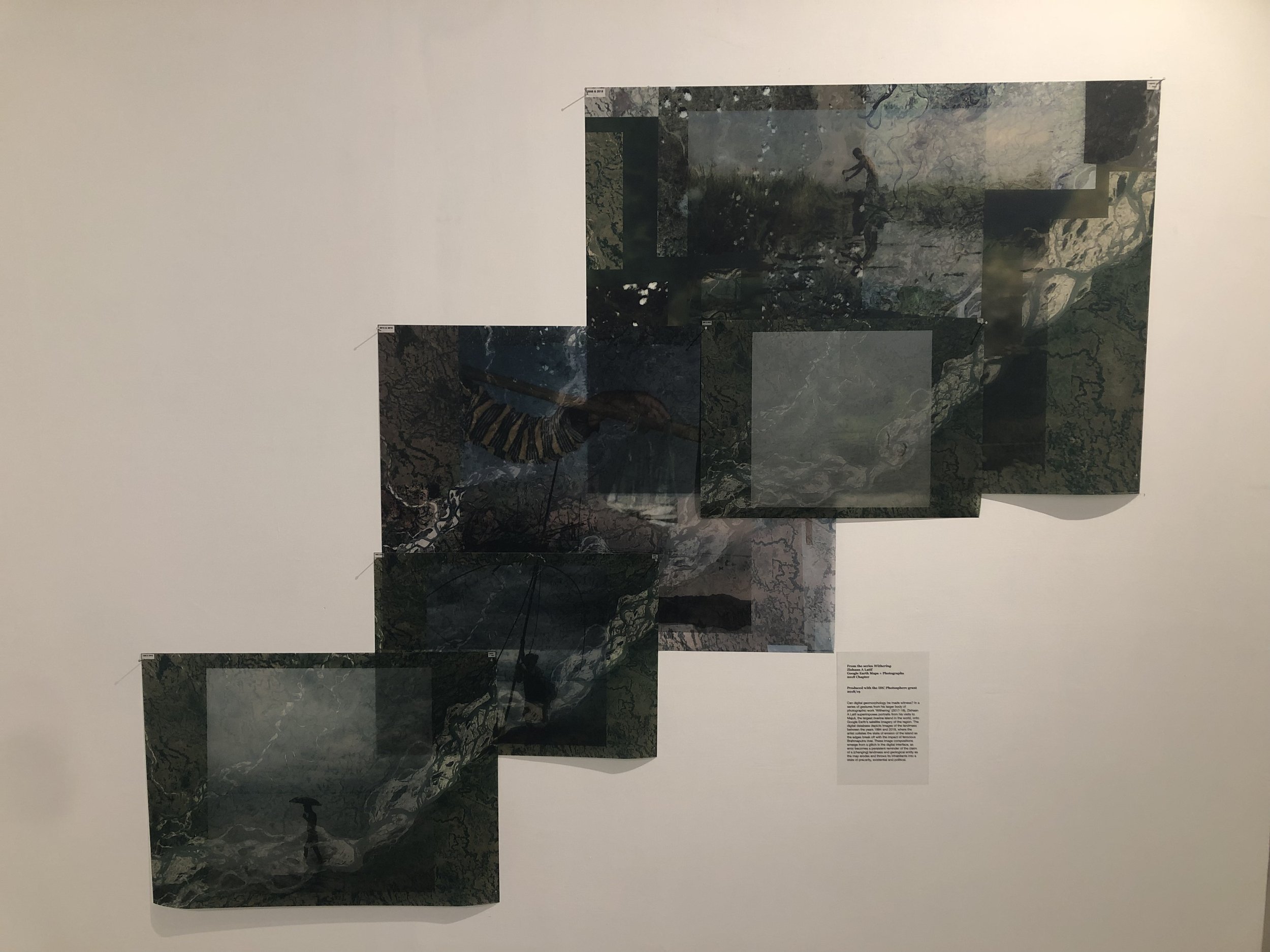

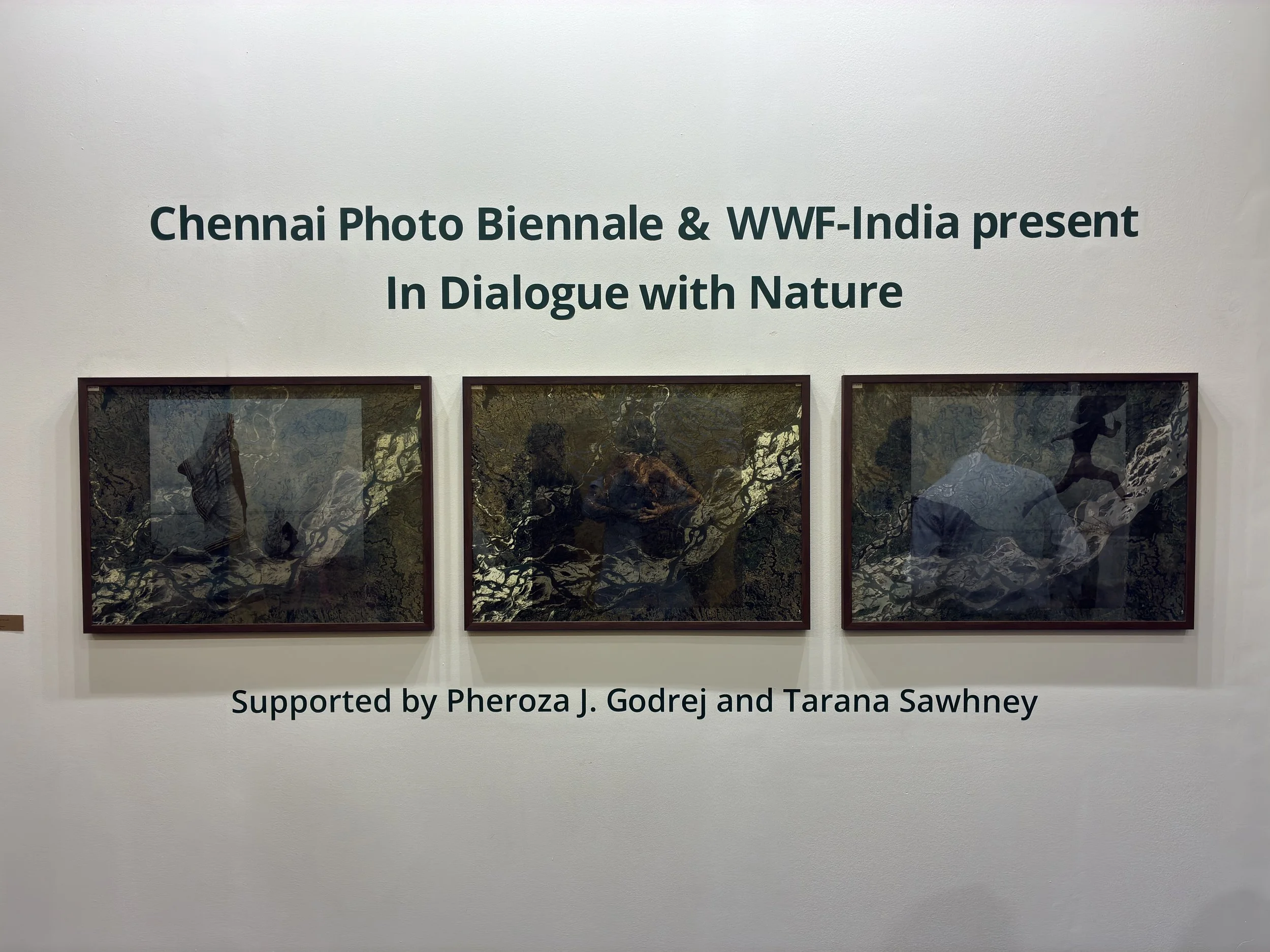

SAT MAPS - This series within ‘Withering’ was purely spurred by an innate instinct to fiddle around, which turned out to only stimulate what I thought would be, a relationship with what was and what remains of the world’s largest river Island - Majuli.

By the year 2000, even satellite imagery starts to get glitchy, a symbolism that cannot escape us in times of surging technology - an irony to the say the least.

“A physical displacement is seen in a digital world with each consecutive year, communicating the palpable shift on ground zero, hence propelling the viewer to better comprehend the disappearing of Majuli over three decades, by overlaying photographs of the islanders, taken in 2018, and satellite imagery of the landmass showing what the region looked like every year from 1984 to 2018, thereby situating their current reality beyond the present moment. ”

'SATMAPS’ showing part of Chennai Photo Biennale curation ‘In Dialogue with Nature’ for WWF India, at India Art Fair February 2026.